If you’ve ever watched a child experience a meltdown, where it can seem to go from 0–100 so quickly, or a shutdown when they seem to suddenly ‘zone out’, it can be confusing, frustrating, upsetting, or all of the above. When this occurs, it’s not ‘defiance’, but the child’s nervous system telling us, “This is too much right now.” This practical guide will explore meltdowns, shutdowns, their differences, what’s happening under the surface, and doable strategies you can try.

Understanding Meltdowns vs Shutdowns

Meltdowns are the ‘fight-or-flight’ response: sometimes loud, physical and intense. The child might hit, throw, scream, or seek strong movement like crashing into cushions. This can help release built-up stress hormones and help reorganise their system.

Shutdowns are the ‘freeze’ response: the brain shuts out stimulation to protect itself. The child might look lethargic, stare into space, close their eyes, or seem unresponsive. They could zone out, rock gently, or put their head on the desk. Both are overload responses, expressed and felt differently.

Research has shown that autistic individuals often have higher levels of stress hormones and that their nervous systems can be more easily taxed during the day. Without the early warning cues that tells the body ‘I’m getting stressed’, these demands can build silently—until the nervous system hits capacity. That’s when we see a meltdown or shutdown. Think of it like a bottle slowly filling with water. When it’s full and there’s nowhere else for the water to go, it spills over.

Stress hormones, you say? What are these?

For those who want a little extra, the main hormones we are thinking about are cortisol, adrenaline, and noradrenaline.

Cortisol: This is the big one. It’s released by the adrenal glands during stress and helps the body respond to threats by staying alert. In autistic children, research shows cortisol levels often stay elevated throughout the school day because everyday tasks — like filtering noise, following group instructions, or managing transitions — require more mental and sensory effort. Think of cortisol like the body’s ‘alert button’ that doesn’t fully switch off.

Adrenaline (epinephrine): This kicks in during acute stress (the ‘fight or flight’). It surges, speeding up heart rate and breathing. It’s why a child might go from 0 to 100 so quickly — adrenaline floods the system when the bucket finally tips.

Noradrenaline (norepinephrine): Works alongside adrenaline to heighten alertness and focus. In overload (fight or flight), it can make everything feel too intense such as lights brighter, sounds louder, emotions sharper.

Spotting the signs: Shutdowns vs Meltdowns at a glance

| Aspect | Shutdowns (Freeze/Collapse) | Meltdowns (Fight/Flight) |

| Looks like | ‘Calm’ (but not actually calm) ‘out of it’ – limp, staring, closed eyes, less responsive, may lie head down, etc. | Big energy – hitting, throwing, head-banging, screaming, running away, etc. |

| Nervous system | Parasympathetic (PNS) ‘brake’ – dorsal vagal response to conserve energy | Sympathetic (SNS) ‘gas’ – fight-or-flight activation |

| Heart rate | ↓↓ Slows down or steady and low | ↑↑↑ Speeds up |

| Hormones | Adrenaline: Low or none (tiny spike just before, then drops)

Cortisol: High (lingering from day’s build-up) |

Adrenaline: High surge

Cortisol: High (build-up + acute surge) |

Common Triggers

- Sensory overload: Sensory environment feels like ‘too much’ – could be from strong lighting, chatter, scratchy uniforms, crowded spaces, the smell of the science room.

- Information overload: Instructions coming too fast, too many instructions and/or the child having delays in processing what’s said. Information becomes too much and overflows their bucket.

- Emotional overload: Big feelings without words to name them.

- Too many demands or unexpected changes: A substituted teacher, cancelled playtime, or feeling out of control.

- Communication hurdles: Struggling to express needs leads to frustration.

When one or the combined weight of these factors pushes a child outside their window of tolerance, their nervous system moves into survival mode, and we see a shutdown (freeze response) or meltdown (fight or flight response).

Supporting regulation during meltdowns and shutdowns: Prevention

Unfortunately, we won’t prevent every meltdown; in fact, I think being supported by a trusted adult to experience big and tricky feelings in our bodies is an important part of development and life. Of course, we don’t want their nervous system to be always in a survival state either!

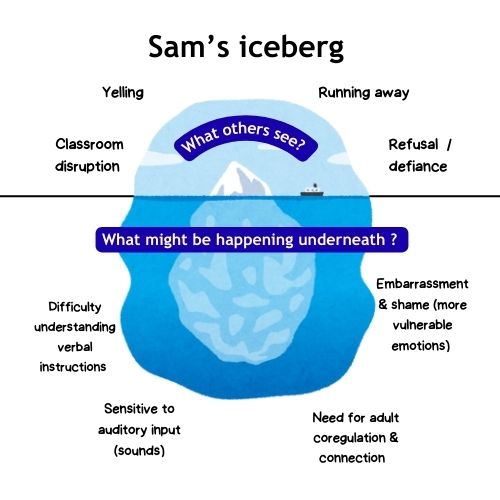

The first steps of intervention planning would be to think about the ‘why’ underneath the behavior. We know that behavior is communication – so what are they communicating to us? I like to use the iceberg when thinking about behaviours:

When we address what is happening underneath the iceberg, it will be far more effective than trying to address the behaviours we might see in a meltdown or shutdown. Sometimes it can be helpful to collect data here, to try to notice patterns, and speak with the child about what is tricky during the day.

General strategies for meltdowns and shutdowns

Modify the environment – reducing unnecessary or overwhelming sensory input while increasing regulating/organising sensory input

- Use visuals and a visual schedule; this can help the child know what to expect by providing extra environmental cues. Helping to create comforting, predictable routines and rhythms.

- Provide information ahead of time so they know what to expect, e.g. transition warnings (e.g. “5 minutes until pack up”). Reducing what is unexpected.

- Reduce unnecessary sensory stimulation—dim lights, minimise background noise, and offer noise-reducing headphones where needed (what needs to be reduced will be different for each person and their sensory processing preferences).

- Use calm corners / reset spaces in classrooms to allow downtime before the child reaches overload. See my blog on reset spaces here.

- Increase access to tools that are regulating for the child, e.g. fidgets, weighted lap pad, music (tools will vary depending on the child’s sensory preferences and arousal levels at that moment in time).

Support exploration of regulation tools – learning to use regulation tools is like strengthening a muscle. It takes time and repetition. No one would expect you to bench 100 kg the first time. We need to build and become stronger bit by bit.

- Practice coping tools when the child is regulated, not during crisis moments. They will be more likely to be able to access the tool in moments of distress if they are really familiar with the tool or strategy.

- Match tools to the intensity/energy of the feeling:

- Lower intensity feelings: you might use thinking strategies (e.g. problem-solving, CBT principles, etc.).

- Higher intensity feelings: use sensory or body-based tools (deep pressure, breathing, movement) that do not require too much cognitive thinking power. For really big feelings where the child has gone into survival mode—it’s just about being safe. Is there a safe spot they can go, or a safe way to let that big energy out?

What to do during meltdowns & shutdowns?

When a child experiences a meltdown or shutdown, they often lose connection to their memory (hippocampus) and thinking parts of their brain (prefrontal cortex). It might be really hard for them to be able to remember what might be helpful, to have conscious control over what they are doing and for them to be able to process verbal information (your instructions of what you are saying).

A meltdown (fight or flight) needs safe ways to release big energy — like pushing against your hands, crashing into cushions, or squeezing a stress ball. While a shutdown (freeze response) needs gentle, low-stimulation, such as dim lights, etc. because in freeze the body is trying to limit the sensory stimuli and input coming in — both start with your supportive presence as an anchor (co-regulation)

The main thing to think about here is safety first, yours and theirs. Some other, more general strategies to think about are:

- Create physical and emotional safety: Move to a quiet space if possible. Think about how you use your body language and voice to convey safety and support regulation. Say less: “I’m here. Let’s breathe.”

- Limit words: Their processing is reduced; long sentences become noise. Skip “You need to stop hitting Johnny”—they might hear hit Johnny. Instead: “Hands down. Safe hands.”

- Name it to tame it: You might like to name what they could be feeling, “I wonder if you are feeling frustrated”—sometimes naming the feeling can help regulate the person. They are seen and heard.

- Remove demands: Pause the task, clear hazards.

- Offer familiar tools: Only what you’ve practiced heaps—never a new breathing technique mid-crisis.

The “Delayed Effect”: When children explode at home

This one is very common. “They’re fine all day at school. Then they explode when we get home.”

So what’s happening here? The child has held it together all day in an environment filled with demands and stimulation, only to release it once they feel safe at home. Teachers may describe them as “fine”, but their body has been accumulating stress hormones all day. Now that they are at home, safe to express their emotions and with a build-up of cortisol, the big feeling can come out over something that we perceive as small—e.g., “we don’t have any crackers left”. This is the straw that broke the camel’s back.

For these children, we still need to tailor our support and approaches the same way we would for a child who experiences meltdowns at school. We also might think about the transition home, and expectations/supports for when they are home to help increase their likely very small window of tolerance after a big day at school. Here are some additional simple ideas for when they are home (try to make it predictable):

- Crunchy snack + deep pressure hug

- 5 minutes on the trampoline or wall pushes

- Cosy ‘getaway spot’ with a weighted blanket and dim lights

There is a great post about this on the Autisum discussion page facebook

Meltdowns and shutdowns are your child’s nervous system shouting “too much” — not defiance — it’s important to be curious about what’s happening beneath their iceberg.

Questions

If you have any questions or need further assistance please do not hesitate to get in touch here or at sophia.occupationaltherapy@gmail.com.